Fabrication First: No Such Thing As Woodworking

There’s No Such Thing as Woodworking

Old crafts are common hobbies. I know a bunch of blacksmiths, glass-blowers, spinners and weavers. It seems like I would fit right in with these ancient crafts, but historically, there’s no such thing as a woodworker. Woodwork is not a craft.

History of Woodcraft

A Period Depiction of 17th Century craftsman. The turner and joiner in this image would not have called themselves woodworkers

As far back as the 1600s, the English government surveyed craftsmen. These early censuses turned up around 2 dozen occupations where an artisan made things from wood. Some of these crafts are familiar; our world still employs a lot of carpenters. Others are pretty rare. Dedicated craftspeople still make wooden barrels or English longbows. But if we surveyed any of the wood-based craftsmen from centuries ago, not one would have called himself a “woodworker.” So many people worked wood for a living that the term would have made no sense. It’s like someone today saying they work with computers. Don’t we all?

It’s all One

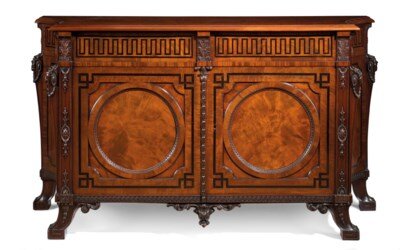

One of the wood trades got much more prominent in the 18th and 19th Centuries: the cabinet-maker. This craftsman specialized in chests, beds, dressers, secretaries (desks), dressing tables and (of course) cabinets. Does this sound familiar? It should; I just described most of modern woodwork. From the Chippendale highboy to the Shaker pie-safe, most modern “woodworking” is really cabinet-making. We think of cabinets as those boxes on the walls of our kitchens, but a cabinet is a whole family of wooden forms based on a rectangle. And most of modern woodwork is dedicated to making these things.

This 17th Century chest of drawers gives us an idea of where the cabinet-maker’s craft was heading in the next century. Photo credit: 1stdibs.com

Somewhere along the line, the cabinet-maker became the much more generic “woodworker.” But how did this happen, and why?

Roots of Modern Woodwork

For many people, the height of pre-industrial furniture making is the work of Thomas Chippendale (1718-1779). Chippendale and his competitors defined craftsmanship and artistry in furniture. These craftsmen produced pieces that were not only expertly constructed, but also featured a blend of styles, exotic woods, daringly curved shapes and advanced techniques like veneer and marquetry. Whatever you think of the style, the 18th Century was probably the high-water mark of Western furniture.

This small chest is a good example of Chippendale’s stylized and highly ornate designs. Photo Credit: Christies.com

This period is the most ornamental and the most technically difficult furniture. Over a century later, as woodwork became the hobby of middle and upper-class men with disposable incomes, this style became the height that many amateur craftmen aspired to. For many “woodworkers” in in the Post-War West, making a Chippendale Highboy was a major artistic accomplishment.

As tastes became more modern and designer/craftsmen like James Krenov and Tage Frid gained popularity, magazines like Fine Woodworking featured their designs as well as Shaker, Arts and Crafts, and even Nakashima-inspired live-edge styles.

Cabinets like these in the “Krenov” style are distinctly modern and lack Chippendale’s fancy touches, but they’re still cabinet work based on straight lines and right angles.Image: Australian Wood Review.

But in general, the craft still leaned heavily on chests, tables, cupboards, and dressers. These are rectilinear forms based around boxes and these kinds of projects still dominate the craft today.

Why the Cabinet?

We all need furniture so cabinet-making is a sensible choice, but making pre-industrial, highly decorated cabinetry is a big challenge.

Especially if you work alone.

Pre-industrial furniture was made in shops filled with workers. Chippendale employed dozens of journeyman and apprentices to handle the stock-preparation, layout, joinery, inlay, carving and finishing of his ornate piece.

For sure, there were some solo craftsmen at the time, but a country carpenter like Jonathan Fisher did much simpler work and made far fewer pieces, working part-time and handling every aspect of production himself.

How can today’s lone woodworker hope to copy the masterpieces of the past? With machines.

The Post War craftsman equipped his garage or basement shop with table saw, bandsaw, jointer, and planer for the basic operations and then probably added a router to help with joinery and molding as well as a lathe for turned components. With this fleet of precision machines, the “modern” woodworker can function as a whole shop.

But it’s not easy.

Paying the Price

Skilled amateurs with machine tools make some inspiring work, but the machines cost thousands of dollars and require considerable space. Most modern machines also involve real danger of injury and a big investment of time. Forget the romantic image of plane shavings falling in a quiet loft. Today’s machine worker does much of his or her work with safety glasses, ear-defenders, and a respirator on. This is industrial work, just on a smaller scale.

This large table saw by the Sawstop company has all the modern features and is unlikely to take your finger off, but it’s also huge and costs thousands.

The cabinet-focused, machine-intensive kind of woodwork also creates a lucrative web of products and services that the woodworking industry can sell. Machines need maintenance, blades, dust-collection, and a thousand accessories and gizmos. These machines take real time to learn and the intimidated beginner is offered a whole array of books, magazines, DVDs, in-person classes and even (ahem) YouTube videos. There’s always more to learn.

Woodwork magazines (which are staffed by talented and thoughtful people) are supported by selling ad space to power-tool companies whose products work best when they’re making box-shaped things from square and stable kiln-dried hardwoods. The articles in these magazines tend to be about using machine tools to make pieces with lots of straight lines and right angles.

Magazines do feature turners, carvers, and experts in marquetry, not only because these “fringe” crafts interest some readers, but also because many period pieces need a little bit of turning or carving to be complete. The modern woodworker must be a jack or jane of all trades, but the focus is still generally on historical cabinet projects.

Strangely Limited

I enjoy magazines like Fine Woodworking and Popular Woodworking; I read them both. But when was the last time you looked at the cover of either of these magazines and saw a bow-maker (boyer) or a wheelwright? Both of these pursuits involve high levels of skill and create impressive wooden objects. Are these craftsmen and women not woodworkers too? Why are they never featured?

I suppose these woodworkers get little attention because they don’t interest readers, but why is that? Probably because the modern woodworker isn’t equipped to make these items. For all the power and supposed flexibility of machine tools, there’s a lot they can’t do. You cannot make a barrel on a table-saw.

Peter Follansbee makes fascinating 17th century reproduction furniture with very basic tools. Hell, the man doesn’t even have a vise on his bench!

When Peter Follansbee released his two books on 17th Century joinery in green wood, he got some flak from reviewers because his methods are “outside the capability of the average woodworker.”

Really?

A man who makes chests and stools out of unseasoned oak with about 30 basic hand-tools is on some other planet? Well, maybe he is. I own a lot of power tools, but I would struggle to adapt them to Follansbee’s work. My table-saw is a Sawstop and its safety mechanism will go off if I cut something green (trust me; I know). If I want to make things Peter’s way, I have to go where he is. I cannot drag his tradition into a machine environment.

This problem reveals the weakness of the machine-centered shop; it’s optimized for cabinet work, but it’s of little use if you want to make other things out of wood. Are you interested in carving wood bowls with an adze? Would you like to make green chairs the way Jennie Alexander taught? Well, that’s very nice, but it’s not “real” woodworking, is it?

Real woodwork is about precision, an attribute that the worker must struggle to attain. A lot of that struggle involves spending money. Does your table-saw have a cast-iron table? It should. Have you used a dial-indicator to remove the slightest wobble from the arbor? Why not? If your work isn’t precise, then it isn’t very good. If your whole style of woodwork doesn’t value (or even need) precision, well that’s just crazy.

The Way Forward

If I’ve been a little critical of modern woodwork, it’s because I love it. I like machine tools, even if I don’t use them much anymore. I like cabinet work…especially when other people do it. My talents lie elsewhere.

You should just know that when most people say “woodworker” what they really mean is “cabinet-maker.” Cabinet-making itself is a fine and noble craft. If you’ve built a reproduction high-boy then my hat is off to you, really. But the cabinet-makers can’t continue to define our craft. We need room for the spoon-carvers, the chair-bodgers, and the whittlers. If you work wood in any way, you belong in the club. And for those of us who make more “unusual” wooden objects we might just have to shoulder our way into the clubhouse.

It’s okay; all that planing has given me a very strong set of shoulders.